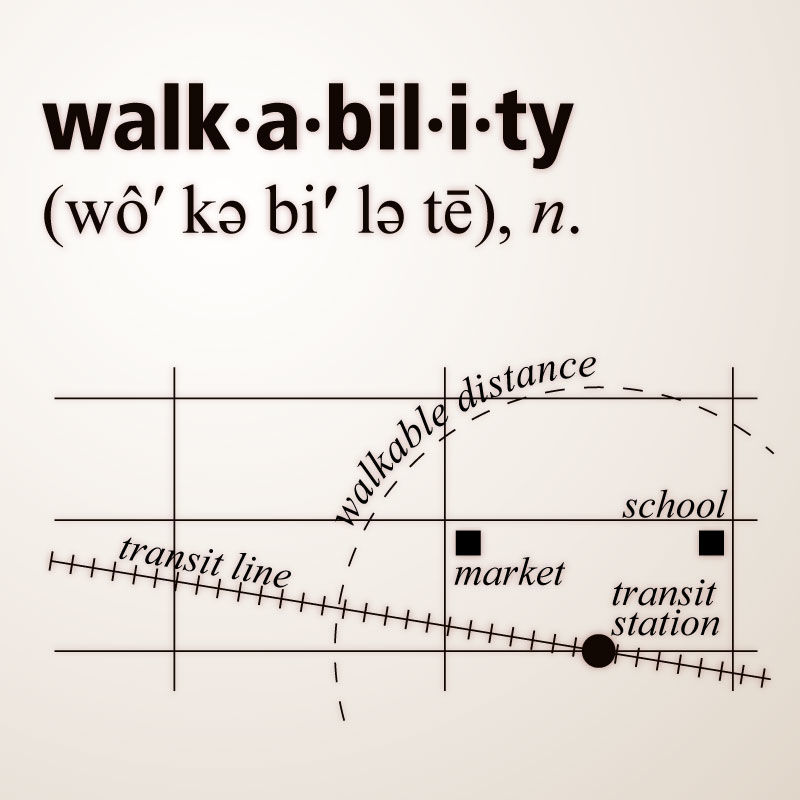

For decades, architects and planners have debated how design and transportation make a place walkable. Usually this results in nostalgic waxing about qualities that make a place a joy to explore on foot, such as “small streets” and “handsome buildings.” While these qualities arguably contribute to walkability, they are difficult to quantify. With the federal government—notably HUD, DOT, and the EPA’s Sustainable Communities Initiative—getting ready to invest in walkable communities, it’s time we consider how to measure walkability.

Many interesting proposals to define walkability have emerged in recent years. WalkScore® has become a home-shopping tool, and realtors now tout a listing’s walkability to prospective home buyers. The Location-Efficiency Mortgage program recognizes that households with lower transportation costs can afford “more house” and buyers are rewarded for purchasing homes near transit. These systems help direct buyers toward existing, walkable development. What’s missing is a formula to direct federal investment toward increasing walkability.

The US Green Building Council’s LEED system may offer a model the government can use. Within a half mile of a rail station? One point. Does the nearest food outlet have fresh produce? One point.

What if we added negative points? Do any roads between housing and retail wider than two lanes lack pedestrian refuges? Minus one point. Is the sidewalk network incomplete? Minus one point, but eligible for funding toward infrastructure.